Blogs

As a Farewell to Benjamin Miller – Two of His Most Significant Woodcuts

By Fr. Johann Roten, S.M.

Benjamin Miller met some of his models and sources of inspiration in Europe, expressionists like Schmidt-Rottluff, Kirchner, and Heckel. He was familiar with the woodcuts of Gauguin and Munch. Two among the early expressionists, James Ensor (1860-1949) and Emil Nolde (1867-1956) left a more immediate imprint on Miller’s work.

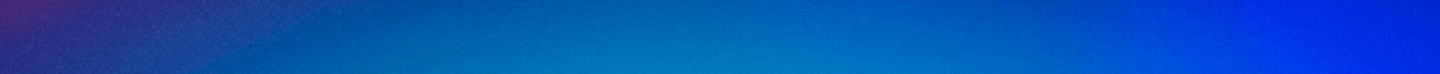

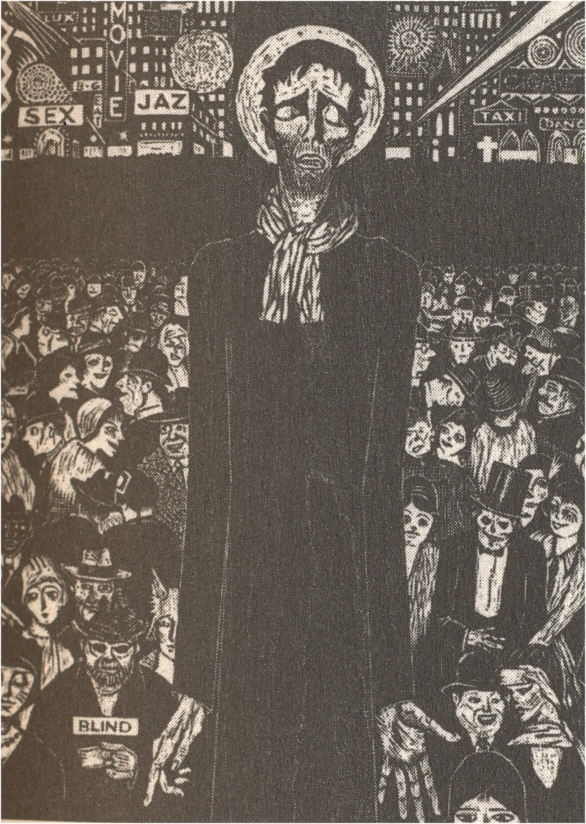

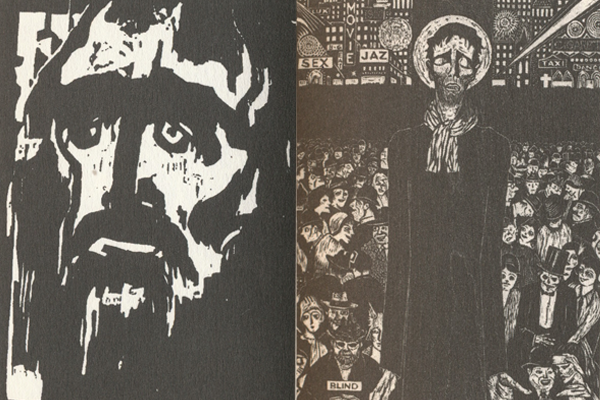

There is no doubt about the great similarity between Nolde’s The Prophet (1912) and Miller’s 1924 woodcut of the same name. Nolde, the painter, is known for his love of vivid colors (Red Poppies, 1920; Sea and Light Clouds, 1935) and a marked religious period in his work (The Last Supper, 1909; The Burial, 1915). However, it was in print making that he found the means to express intense emotions in a radically simplified form. His most celebrated wood cut is The Prophet. The woodcut is hailed for the masterful combination of fluidity of form and intensity of expression. The hollowed eyes, furrowed brow, and sunken cheeks point to the ascetic, whereas the overall impression denotes a thoroughly spiritualized existence. Recovering from illness in 1909, Nolde saw in The Prophet a symbol of his conversion and of religiosity as such. Miller’s Prophet is more artisanal, in form as well as in expression. Eyes and face are haunted by what the prophet sees or blindly intuits. The Prophet is an early example of Miller’s print making. At the same time, his woodcut is typical of the suffering and critical look with which the Cincinnati artist perceived human reality and his own time.

There is a second woodcut which points in a similar direction. Hailed as his most famous work, The City (1928) can be understood as a “secular sermon.” The 1930 publication of The New Woodcut commented as follows: “It is scathing satire on the fatuous frivolity and extravagance supposed to be rife in New York and presumably in other cities, regardless of the needs of the suffering poor, a crowd of inane faces of men and women of every description, laughing and giggling.” (A. Bernard, 17). The grinning and leering masses are pressing forward, literally pushing the Christ figure out of the picture. Oversized, but blind and empty handed, Jesus is an image of crucified impotence, a gigantic shadow without power, an irritating obstacle on the ways of the world. Miller’s secular sermon is reminiscent of James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels (1888). Rejected in the beginning, the first public exhibit took place in 1929, the contrast and similarity with Miller’s oversized Christ is easily perceived. Ensor’s diminutive Jesus, sitting on a donkey, is swallowed up by the same grinning and leering masses as in Miller’s woodcut. There is no singing, there are no palm branches on his way to Jerusalem. Ensor’s painting has primarily political significance, and his opinion on religion at that time bordered on cynicism. Miller, on the contrary, fustigated the cynicism of the masses on behalf of the poor, the downtrodden, and the poorest of all, Jesus.