Orthodox Tradition and Mary

Orthodox Tradition and Mary

Mary in the Orthodox Tradition

Living with Mary Today Symposium, University of Dayton July 26-29, 2006

– Virginia M. Kimball

Eastern Orthodox churches today, to be differentiated from Roman Catholic communions of the Eastern Rite, are those churches which find their apostolic head in the Patriarchate of Istanbul -- described theologically as standing in the Byzantine tradition. Enthusiastically and fully mindful of Christianity’s historic beginning, today we must remind ourselves of the important ecumenical relationship between Bartholomew, Patriarch of Eastern Orthodox Christianity in Istanbul (former Constantinople), and Benedict XVI, Roman Catholic Pope in Rome. Their relationship is truly brotherly, a familial brotherhood, reminiscent of the Apostle Andrew, the first patriarch of Constantinople, whose brother was the Apostle Peter in Rome. Today, following a mutual lifting of anathemas in 1964 by Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras, there is no longer a chasm of alienation between the Eastern Orthodox churches and the Roman Catholic Church. Neither continues to consider the other heretical or schismatic. Both recognize the true sacraments of the other, with Christ at the center. Of course, there are still deep scars from the historic past and vast gulfs between these two religious cultures of East and West, but it is obvious that the beloved Pope John Paul II of blessed and fond memory had a heart for ecumenism and appealed to Catholics worldwide to appreciate the ancient eastern liturgy and its iconographic tradition. From this point of view, we will examine Virgin Mary in the “Orthodox Tradition,” finding that it is not to be compared as a different way of knowing Mary but perhaps a shared way that probes and perhaps rediscovers profound mystical depths of a living faith unified in Christ, Mary’s son.

Orthodoxy and its teaching is fundamentally experiential, expressed over centuries in liturgical prayer and related iconography, and always understood as an encounter with truths that have at their heart the life and teaching of Jesus. Father John Meyendorff, in a critical study of Byzantine Theology, described the Orthodox theological point of view which equates theology and holy living.

Because the concept of theologia in Byzantium, as with the Cappadocian Fathers, was inseparable from theoria (“contemplation”), theology could not be – as it was in the West – a rational deduction from “revealed” premises, i.e. from Scripture or from the statements of an ecclesiastical magisterium; rather it was a vision experienced by the saints, whose authenticity was, of course, to be checked against the witness of Scripture and Tradition. … The true theologian was the one who saw and experienced the content of his theology; and this experience was considered to belong not to the intellect alone (although the intellect was not excluded from its perception), but to the “eyes of the Spirit,” which place the whole man – intellect and emotions, and even senses – in contact with divine existence.1

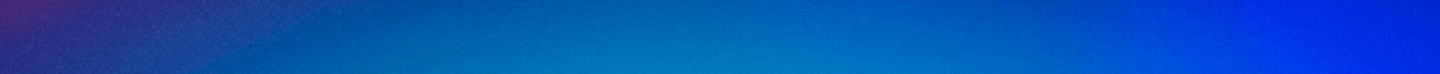

When considering Mary, the mother of Christ, in Orthodoxy, one looks naturally and directly to the liturgical tradition. Liturgy not only includes prayers, hymns, antiphons, and biblical readings of the Divine Liturgy and liturgies of all feast days of the year, but also an iconographic tradition closely knit with the liturgical tradition. Icons are truly never separated from liturgical meaning. The experience of “knowing” Mary is primarily realized in the chanted prayer of the liturgy and in reverence for icons. In Catholicism, well-known images of Mary most often are crafted in a humanistic style, particularly by Renaissance and Baroque masters. In modern times, many images connected with apparitions have become popular, such as the Virgin of Guadalupe and the Virgin of Medjugorje. In the Byzantine tradition, images of Mary, the mother of Christ have been, since their very origin, rather surrealistic in style, purposely trying to avoid the question: “What did or does Mary really look like?” The image of Mary in the Byzantine icon is always related to her motherhood, to the primal concept of the theological title “Theotokos,” bearer of God. She points to her Son showing the way in an icon called the Hodegetria. She embraces her Son, flesh to flesh, motherly care touching godly care in the icon called the Eleousa. She entreats her Son with out-stretched arms in prayer at the foot of the cross and often from the left side of the Royal Gates on the icon screen of an Orthodox church, called the Deesis. If we assign Christological terms to these Marian images, we say the Hodegetria demonstrates her Son’s divinity, the Eleousa demonstrates His humanity, and the Deesis shows us Mary, Christ’s mother, petitioning her Son’s help, thereby indicating the Son as the source of salvation.

Here are examples of these icons2 of Mary:

The Hodegetria – See how Mary’s hand “points the way.” She tells those who pray with this icon that Jesus is Her Son who is the “Way” to life and true joy. He is the Author of Life, divine in His very being.

The Eleousa – See how Mary touches the Child, flesh to flesh, in a tender, loving and motherly way. She tells those who pray with this icon that her Son, Jesus, is truly human, truly a child to encounter with human touch and response.

The Deesis – See how Mary stretches forth her arms in petition, connecting to Her Son through prayer. She tells those who pray with this icon that she is entrusting not only her own cares and needs to her Son, but embraces those who pray with her for God’s life and true joy.

Standing center in Orthodox tradition concerning the Virgin Mary is a singular concept. She is the Theotokos, the woman who bore the life-giving God into human life. Any other title or characterization of this woman, who bore Christ, has to stand on this core truth. The major feasts of the Church, those which celebrate the events of Christ’s life, all have a Marian element. In the traditional liturgical year’s cycle of these events, there is always a “synaxis” on the day that follows an event of salvation history. For instance, the synaxis of the Feast of the Nativity celebrates the motherhood of Mary. Within the Divine Liturgy, Mary is always granted esteem because she is the Theotokos. Immediately following the Anaphora (lifting up of gifts) and the Consecration in the Divine Liturgy of St. Chrysostom, the famous hymn Axion Estin is always sung, recognizing Mary’s role in the miracle of the Eucharist:

It is truly right to bless you, Theotokos,

ever blessed, most pure, and mother of our God.

More honorable than the Cherubim,

and beyond compare more glorious than the Seraphim,

without corruption you gave birth to God the Word.

We magnify you, the true Theotokos.3

Mary, a young Hebrew woman, is the one human being to be praised by the angels of Heaven, who is ever blessed (filled with joy), most pure (filled with God’s presence and holiness), and mother (one who bore, nourished with her breasts, and raised up the man Jesus.) What can the believer do but magnify her, which is to raise her in esteem above all the inhabitants of Heaven.

Other than the many icons which celebrate Mary’s involvement in the life and work of Christ, in particular the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Crucifixion, the Ascension, and Pentecost, there are a host of other icons that magnify her cooperation with God’s plan of redemption and exemplify her life as a promise to all the faithful of God’s goodness, in particular the icon of the Dormition. Tradition teaches that at her death, Mary’s tomb was found empty. Most believe that she was taken from her burial site by her son to be with Him in Heaven. Others believe that perhaps she, too, awaits the final days to experience resurrection, but this is often the minority opinion. In every icon, there is a fathomless depth to the mystery of God that can be experienced in prayer and through contemplation of the icon.

No one knows the actual appearance of the Theotokos, but there is a strong, legendary tradition that she was painted by St. Luke. Whether or not there is truth to this legend, most Byzantine iconography portrays her with a characteristic appearance which involves: a narrow Semitic face, a long and slender nose, and dark brown eyes. Look for these features in ancient Byzantine icons, mentioning for example “the Mother of God, Salus Romani,” an 8th century icon found at Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome.4

Orthodoxy does believe, as do western Christians, that miracles can occur in connection with an icon. To delve into the history of miraculous icons of the Theotokos, is to open a search into the mystery of God that stretches far back into history and includes literally hundreds of icons. An illuminating article on this subject is found in Mother of God, Representations of the Virgin in Byzantine Art, a publication of the Benaki Museum in 2000. Alexei Lidov described the inherent academic difficulty in studying miracle-working icons:

A study of the stories about miracle-working icons could become a special sphere of research requiring the joint efforts of historians, art historians and philologists. Promising research areas are the study of the structure of these stories and of the interrelationship between archetypal, legendary, literary and real historical motifs. One of the difficulties is that archetypal models are sometimes not invented by the author, but are an integral part of the actual event.5

Lidov does, however, point out the value in studying the miracle-working icons of many centuries: “We immediately discover the important fact that a great deal of valuable historical information often not to be found in other sources has accumulated around the miracle.”6

Two well-known feasts reporting a miraculous aspect in Mary’s work and which also are associated with important liturgical feasts in most Orthodox traditions (especially Greek and Russian) are interesting to the ecumenical discussion of Mary as Mediatrix. They represent spiritual gifts that come to the faithful through the Theotokos, demonstrating a tradition of supplication to the Virgin Mary long before church divisions. The first feast, Theotokos of the Life-Giving Fountain, recalls an event in the 4th century in the environs of Constantinople. A young man who was to become the Byzantine Emperor, Leo the Great, was out for a daily walk when he heard the cries of a blind man with a critical thirst for water. At first, not finding any water to help the blind man, the young man then heard the voice of a woman calling him to a place of water. The place became a place of healings. The tradition of the Theotokos who gives Life-giving water, or she who metaphorically is the “Source of the Source” -- that is she who is the source of Christ’s healings as represented by water, became an important feast celebrated today on the Friday following the Great Pascha, Easter. The Friday after Easter in “Bright Week” in most Eastern Orthodox churches is a surprisingly joyful celebration of Christ providing life and sustenance, physically and spiritually, to all the faithful, through his mother. The Fountain shrine is still present today, just outside modern Istanbul, having been built, destroyed and then restored many times throughout the centuries. The feast of the Theotokos of the Fountain, like all other Marian feasts, signifies a significant theological truth, in this case how Christ is the well of life, and his mother is but the fountain.7

ICON: Theotokos of the Fountain – See how Virgin Mary represents a fountain within a fountain, a source flowing with the waters of life which in reality flow from from the Source, her Son.8

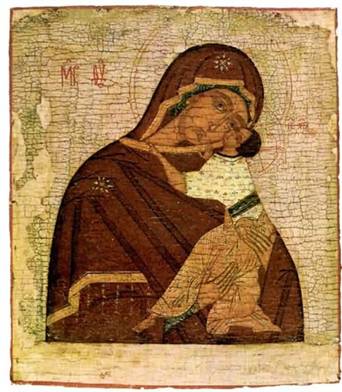

Yet another important icon and feast day is that of “The Theotokos of Blachernae, The Virgin of Protection.” This miraculous occurrence, dated vaguely between the 5th and 10th centuries, tells the story of Virgin Mary appearing upon the bema of the altar at a shrine housing the relic of her belt in Constantinople. In this appearance of Christ’s mother, she was seen opening her cloak, the veil covering her shoulders, and beneath it were seen the faithful gathered in her motherly care. Again, the theological consideration is that she is offering protection and shelter that comes from her Son, the Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.

Yet another important icon and feast day is that of “The Theotokos of Blachernae, The Virgin of Protection.” This miraculous occurrence, dated vaguely between the 5th and 10th centuries, tells the story of Virgin Mary appearing upon the bema of the altar at a shrine housing the relic of her belt in Constantinople. In this appearance of Christ’s mother, she was seen opening her cloak, the veil covering her shoulders, and beneath it were seen the faithful gathered in her motherly care. Again, the theological consideration is that she is offering protection and shelter that comes from her Son, the Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.

ICON: Theotokos of Protection9

– See how Virgin Mary appears in this representation holding her veil, appearing as the tradition says, from the sanctuary of the chapel, offering care to those gathered around her. The lower part of this icon speaks of Romanos the Melodist, a later poet who composed many magnificent chants in honor of the Theotokos, seen on the day he is said to have composed a truly inspirational hymn for the Feast of the Nativity. This whole icon has many elements that tell several stories at one time.

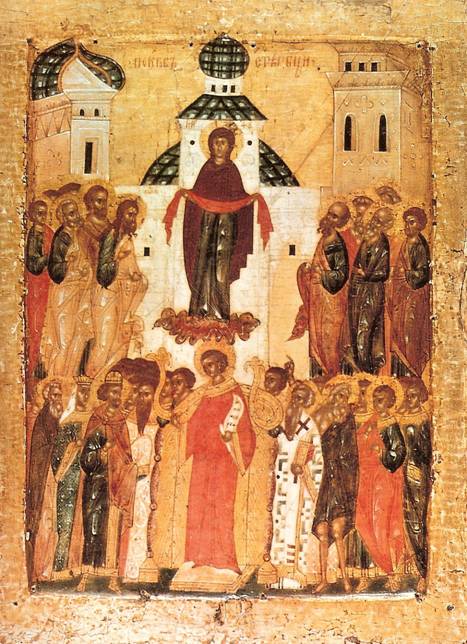

Later, and related to the Virgin of Protection, an icon of Mary with her open cloak and Christ the child blazoned upon her breast, became an image replicated throughout the Byzantine empire on coins, sacred vessels, icons, and objects of private prayer. The icon of the Platytera, Virgin with her womb wider than the heavens, appears related to the image of the Theotokos of Protection. The Platytera is seen in many Orthodox churches, modern and ancient, in the apse or wall behind the main altar, revealing that she is the mother of the Lord who comes to us in the mystery of the sanctuary. There is an ancient Platytera in the ancient church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople.

Icon: Platytera10

A beloved title for the Theotokos in the Orthodox tradition is that of “the Panagia.” This term theologically relates most closely to the Roman Catholic dogma of the Immaculate Conception. In the sense of this title, Mary is completely holy, truly blessed and pure. The difference in the theological concepts concerning mankind’s nature and the result of sin as they relate to Virgin Mary, “Panagia” for Orthodox theology and “Immaculate Conception” for Roman Catholic theology, rests mainly on two terms that are commonly used in the ecumenical discussion between Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism – that of the theological understanding of “the Fall” for Orthodox theology and that of “Original Sin” for the Roman Catholic theology. Additionally, a further theological distinction has been discovered in the ecumenical exchange, that being that the Orthodox theologian prefers to speak of “the Fall” in terms of “justice or more specifically justification” and the Roman Catholic theologian tends to speak of the “juridical effects” of “original sin.” In over-simplistically stated terms, this means that the Orthodox view the salvific work of Christ more from a point of view of “justification,” where the Roman Catholic theologian views the salvific work of Christ as a satisfaction for the sin of mankind in a juridical way. In 1986, in an ecumenical discussion between Roman Catholic theologian Edward Yarnold SJ and Orthodox theologian Bishop Kallistos Ware, at an Ecumenical Society of the Blessed Virgin Mary meeting in Chichester, England, we find that these two theological positions may not be as untenable as we think. Bishop Kallistos agreed that he did not find himself “so very far apart from [Father Yarnold].”11 Father Yarnold described the human condition, after Adam and Eve sinned against God, to mean that humans come into the world with a “God shaped hole in their hearts,” that “the sin of the race causes each to come into this world with this God shaped hole unfilled, with this capability of receiving the Holy Spirit unrealized … an inherited spiritual defect.” However, “because of the work for which God destined Mary, that God shaped hole was never left unfilled, there was never in her a lack of original justice.”12 Bishop Kallistos stated he believed Virgin Mary was “from the very beginning of her existence … filled with grace for the task which she had to fulfill.” He responded affirmatively to Fr. Yarnold in saying: “Do I, as an Orthodox accept that, from the very beginning of her existence the Blessed Virgin Mary was filled with grace for the task which she had to fulfill? My answer is emphatically, Yes, I do believe that. But I also believe that she was given a fuller measure of grace at the Annunciation,”13 referring to the pouring out of the Holy Spirit to Mary at the moment of her fiat.

Bishop Ware explained that the Christian East sees a “continuity of sacred history” throughout the ages, putting the Mother of God in a line of humans who were seeking God in a prophetic and holy way, in a kind of growing closer and closer to the coming of salvation for humanity. Mary was “involved in the total solidarity of the human race, in our mutual responsibility”14 for the Fall.

Simply said, Orthodox theology thinks of the young Hebrew woman Mary of Galilee as a human like any other human who was or has ever been born. Her all-holiness was not a privilege, but truly a free response to God’s call. She was filled with the Holy Spirit and answered a total “yes” to the call of God’s plan for salvation.

Orthodox theology considers that humanity “fell” from God in the sin in the Garden, but that humanity continues to be born in the “image of God, (GN 1:27)” throughout the subsequent ages with the same integrity of human nature as Adam and Eve before their disobedience. The world, however, in fact the cosmos, into which subsequent human beings are born, is broken. They are whole and made in the image and likeness of God but come into a world that is filled with sinfulness. The Theotokos came into the world embracing a beautiful “imago Dei,” and received a fullness of God’s grace at the Annunciation that prepared her for her task. The fullness of the Holy Spirit came upon her with her agreement and for the subsequent Incarnation (Lk 1:35): “And the angel said to her in reply, ‘the Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you.’” In yet another ecumenical paper, Bishop Kallistos wrote:

Mary is an icon of human freedom and liberation. Mary is chosen, but she herself also chooses. Luke’s narrative speaks not only of divine initiative but also of human response, setting before us the entire dialectic of grace and freedom. Mary was predestined to be Mother of God, but she was also free.15

Orthodox theologian Dr. George S. Gabriel, in his book about the Theotokos entitled Mary the Untrodden Portal of God, contrasts the concepts of the all-holiness of Mary and Mary as Immaculate Conception:

The dogma of the Immaculate Conception severs Mary from her ancestors, from the forefathers, and from the rest of mankind. It marginalizes the preparatory history and economy of the Old Testament as well as the true meaning and holiness of the Theotokos herself. By severing her from fallen mankind and any consequences of the fall, this legalistic mechanism makes her personal holiness and theosis nonessential in the economy of salvation and, for that matter, even in her own salvation. Moreover, “it places in doubt her unity of nature with the human race and, therefore, the genuineness of salvation and Christ’s flesh as representative of mankind. [Qutoing, A., Yevtich, TheTheotokos: Four Homilies on the Mother of God by St. John of Damascus, 3].”16

For many Catholics, this theological debate concerning “Immaculate Conception” versus “the Panagia” is upsetting. However, in the ecumenical world there are three steps that have been discovered for churches to move forward together: 1) all must repent, 2) all must listen, and 3) all must reflect. In the Orthodox mind, words can bind down the mystery of God and words of dogmas about the Virgin Mary can become a problematic division. Ultimately, it will be those theologians, both Orthodox and Catholic, who approach these theological questions in the spirit of repentance, who pray, and who listen intently to each other, who will enlighten us further and perhaps find a ground of union. The experience of the mystery of God in liturgy and iconography of the ancient eastern tradition may help to resolve this conflict.

On another theological issue, which Protestants often question, can we say that Mary, the mother of Christ, is to be called “ever Virgin”? Undeniably, it is the Patristic heritage that upholds this truth of faith in the affirmative. The title “ever a virgin,” aeiparthenos, dates probably in its terminology to the 4th century. Origen refers to this idea of the perpetual virginity of Mary, and St. Athanasius clearly upholds it. From patristic times, Joseph is considered to be a widower who took on the responsibility of young Mary, as chosen to do so by his temple community. The brothers and sisters of the Lord, as mentioned in the New Testament, are consequently considered, in Orthodox tradition, to be Joseph’s children.

There are two special liturgical prayers of significant length that are important in the Orthodox tradition – the Akathistos (translated as “not sitting”) and the Paraklesis (Supplications to the Virgin). Again, there is a strong connection between these liturgical prayers and an iconographic tradition. The Akathistos hymn which is, in itself, a service prayed weekly throughout Great Lent, centers on the mystery of the Incarnation. Authorship is attributed to 5th-6th century hymnist Romanos the Melodist, but scholars find that his sources for the magnificent chanted poetry may have actually derived from more ancient Syriac poetry. The hymn, probably popular for many years for supplication to the Virgin Mary, was sung at a moment of crisis in the 10th century when Constantinople was menaced by invading marauders, the Avars. The legend is told that the people stood and sang the hymn all night long and the city was subsequently saved, thereby giving the title to the hymn, “Not Sitting.” In the Akathistos, a deeply mystical response is sung to repeated greetings of joy regarding the Theotokos. The greeting is a paradoxical phrase repeated over and over in the Akathistos, showing Orthodox regard for the mother of Christ to be awe-filled and beyond any kind of absolute comprehension. It is a phrase that portrays Mary, the mother of Christ, as one who experienced a betrothal with God, a spousal relationship that represents God’s offer of love and hope for response that is actually deeply biblical. The hymn represents a series of salutations to Mary, such as “Rejoice, To You through whom joy shall shine forth. Rejoice! To You through whom the curse will vanish. Rejoice! The recalling of the fallen Adam. Rejoice! The redemption of Eve’s tears. Rejoice! O height beyond human logic. Rejoice! O depth invisible even to the eyes of Angels. … Rejoice, Bride Unwedded.” Each section ends with the remarkable, “Rejoice, bride unwedded (Chaire, nymphe anymphete).” In the paradox, lies a remarkable mystery of spousal love that God offers.

In the ancient centuries of the Eastern Church, icons were connected with the singing of the Akathistos hymn. Most often, long processions would wind through narrow streets from shrine to shrine, with faithful singing the many verses of the hymn while carrying an iconographic banner or icon on stands.

The Service of the Small Paraklesis to the Most Holy Theotokos, is a liturgical service sung in the two-week Lenten period before the Feast of the Dormition, (paraklesis refers to a kind of salutation and petitioning set of prayers.) It is one of the most popular of Marian hymns and obviously demonstrates, that from ancient times Mary, the mother, is considered the mediator of the love and care of Her Son. The concluding verse of the Small Paraklesis in itself demonstrates the importance of her mediation as well as the humility of her motherhood:

I have you as Mediator

Before God who loves mankind;

May He not question my action

Before the hosts of the Angels,

I ask of you, O Virgin

Hasten now quickly to my aid.

You are a tower adorned with gold,

A city surrounded by twelve walls,

A shining throne touched by the sun,

A royal seat for the King,

O unexplainable wonder,

How do you nurse the Master?17

To enter an Orthodox Church building is to enter into the tradition of an ages-old spiritual culture where the faithful can prayerfully encounter Mary and her Son in liturgical prayer and iconography. Such an experience is discovered in liturgical chant and icons. One lights a candle and brings his or her own living light into the place of prayer. Then, it is the custom that one regards the icon of the Theotokos, bends, kisses the Child in her arms thus revering the Mother who bore Him. One then enters the community and joins the voices of joy and petition that abound, offering a sacrifice of one’s heart and one’s hands. One can’t avoid the icon of the Platytera offering her Son from the holy altar. One receives the Body and the Blood of Christ as Mary, Christ’s mother, received the body and blood of God’s son. One prays for those departed to God’s hands. On leaving the church building, one sees the icon of the Dormition above the departure way. One reflects. It is time to live the rest of one’s life with hope that Mary’s Dormition is the promise, the promise of a life with Christ that will never end. This is the Orthodox way, living with Mary.

© Virginia Kimball, Adjunct Professor, Department of Theology, Merrimack College, North Andover, MA September, 2006

[1] John Meyendorff, Byzantine Theology, Historical Trends and Doctrinal Themes (New York: Fordham University Press, 1979), 8-9.

[2] These three icons, Hodegetria, Eleousa, and Deesis are found on Orthodox Photos, http://www.orthodoxphotos.com/Icons_and_Frescoes/Icons/Mother_of_God/index.shtml

[3] “Online Chapel,” Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, The Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, http://www.goarch.org/en/Chapel/liturgical_texts/liturgy_hchc.asp (Accessed July 20, 2006.)

[4] Image found on website, http://www.iconsexplained.com/iec/00351.htm (Accessed July 20, 2006.)

[5] Alexei Lidov, “Miracle-working Icons of the Mother of God,” in Mother of God, Representations of the Virgin in Byzantine Art, edited by Maria Vassilaki (Skira Editore, Milan, Italy, and Benaki Museum, Athens, Greece, 2000), 49.

[6] Lidov, 47.

[7] Virginia Kimball, Liturgical Illuminations: Discovering Received Tradition in the Eastern Orthros of Feasts of the Theotokos, Doctoral Dissertation, International Marian Research Institute, Dayton, Ohio, 2003.

[8] Icon Gallery, Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, http://www.goarch.org/en/resources/clipart/icondetail.asp?i=95&c=Theotokos&r=lifegivingfountain

[9] Icon of the Theotokos of Protection, privately owned by author.

[10] Platytera icon, apse and iconostasion, St. George’s Antiochian Church, Lowell, MA, http://www.saintgeorgelowell.org/photo14.html

[11] Bishop Kallistos T. Ware and Edward Yarnold SJ, “The Immaculate Conception, A Search for Convergence,” Ecumenical Society of the Blessed Virgin Mary, ESBVM Congress, Chichester, England, 1986, 11.

[12] Ware and Yarnold.

[13] Ware and Yarnold.

[14] Ware and Yarnold, 6.

[15] Kallistos Ware, “Mary Theotokos in the Orthodox Tradition,” The Ecumenical Society of the Blessed Virgin Mary, 1997, 14.

[16] George S. Gabriel, Ph.D., Mary, the Untrodden Portal (Thessalonica and Ridgewood, NJ: Zephr, 2000), 68.

[17] The Service of the Small Paraklesis (Intercessory Prayer) to the Most Holy Theotokos, translated and set to meter by Demetri Kangelaris and Nicholas Kasemeotes (Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1984), 37-38.

All About Mary includes a variety of content, much of which reflects the expertise, interpretations and opinions of the individual authors and not necessarily of the Marian Library or the University of Dayton. Please share feedback or suggestions with marianlibrary@udayton.edu.