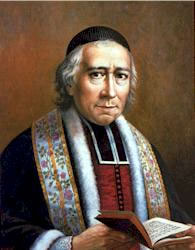

Meet 3 Remarkable People Who Got Us Started

He Narrowly Escaped the French Revolution Only to Discover His True Calling.

William Joseph Chaminade (he took Joseph as his Confirmation name and preferred it) was the second youngest of 15 children of Blaise Chaminade and Catherine Bethon. Born in Perigueux, some 60 miles northeast of Bordeaux, he went at age of 10 to the College of Mussidan, where one of his brothers was a professor.

First as a student, then as teacher, steward, and chaplain, he remained at the college for 20 years. The turmoil that marked the beginnings of the French Revolution forced him to leave. Except for three years in exile, he spent most of his long life in Bordeaux itself.

Church in Hiding

It was during the most trying period of the Revolution, when persecution had forced him to go underground because of threats on his life, that Chaminade met Marie Thérèse Charlotte de Lamourous.

She was a very important part of the Catholic community that continued to carry on its spiritual mission in most difficult circumstances. The Archbishop de Cice was in exile; the churches, when they were open at all, were in the hands of Constitutional clergy — those who had taken the schismatic oath of allegiance to the revolutionary government. Priests such as Chaminade, who refused to take the oath, were forced into hiding and had to go about in disguise.

It was the laity — women in particular — who preserved and passed on the teachings of Christianity; formed a communication network for the priests who refused to take the civil oath; distributed the sacraments; and provided moral encouragement to the dying, including imprisoned priests awaiting execution; instructed the young; supported the weak; and witnessed, sometimes at the cost of their lives, to the power of Christ at work within them.

Chaminade carried on this ministry in Bordeaux from 1791-1797, openly when he could, secretly when he had to. So successful was he in disguising himself and concealing his hiding places that the police, after numerous fruitless attempts to find him, declared he must have left the city. That meant his name was carried on the official lists of the emigres, which contained the names of those banned from returning to France.

In a moment of relative tolerance in 1797, he came out of hiding to exercise his ministry openly. But a sudden shift in the political situation caught him off guard.

He was falsely accused of having returned from exile without permission and was forced to leave France. Taking refuge in Spain, he spent three years in Saragossa praying at the shrine of Our Lady of the Pillar, sharing life with thousands of other exiles, and planning for an unknown but hoped-for return to France.

With the end of the Revolution in 1800, he returned to Bordeaux. Appointed administrator of the badly devastated Diocese of Bazas, he managed to restore it to some semblance of normalcy within two years. At the time, he began in Bordeaux a work that would occupy him for the next 50 years.

Beginnings of 'Sodality'

Chaminade gathered together a number of young men and women, many of whom he had known before and during the years of persecution and formed a "community" of mutual support and Christian outreach that attracted people from all sectors of society and parts of the city.

He first worked in limited and temporary quarters, but in 1804, he established the permanent headquarters for his work in the former chapel of the Madelonnette Sisters. The site became the center of the Sodality of the Madeleine. It remains today in the hands of the Marianists and is a vital urban church in Bordeaux.

Chaminade's concept of the Sodality was to gather all Christians — men and women, young and old, lay and clerical — into a unique community of Christ's followers unafraid to be known as such, committed to living and sharing their faith, and dedicated to supporting one another in living the Gospel to the fullest.

The enterprise was placed under the patronage and protection of the Virgin Mary. As his own insights developed, he came to see the Sodality as the Marianist Family, dedicated to sharing her mission of bringing Christ into the contemporary world.

It was characterized by a deep sense of the equality of all Christians, regardless of state of life; by an energizing spirit of interdependence; by effective concern for individual spiritual growth; and by the desire, in Chaminade's words, of "presenting to the world the amazing and attractive reality of a people of saints."

Side by side with him in this endeavor was Marie Thérèse, who headed up the Young Women's and Married Women's sections of the Sodality.

Creating a Marianist Family

At the same time that Chaminade was administering the Diocese of Bazas and inaugurating his work with the Sodality, he was also encouraging and assisting Marie Thérèse in her efforts to provide an environment where prostitutes desirous of changing their lives might find the support they needed.

In 1808 he became aware of the work that Adèle de Batz de Trenquelléon and her associates were doing in the Agen area, some 60 miles upstream on the Garonne River.

Similar in many ways to the Sodality of the Madeleine, her Association affiliated with his in Bordeaux.

Out of the Sodality developed the Institute of the Daughters of Mary and the Society of Mary — the two Marianist religious orders in the Marianist Family.

These three foundations — the Sodality of the Madeleine, the Institute of the Daughters of Mary and the Society of Mary — are considered the wellsprings of the Marianist charism.

They have common characteristics, a common spirit, and the same goals and purposes. And they all continue today as various segments of the Marianist Family.

Dedicated to the Mission of Mary, She Brought Hope to a Broken World.

Like Marie Thérèse, Adèle was of noble birth; unlike the former, she was of a wealthy and aristocratic family.

Her father, the Baron de Trenquelléon, was an officer in the king's own Royal Guard. When Adèle was two-and-a-half years old, he voluntarily went into exile to support the anti-revolutionary movement.

In 1797 the baroness and her two children were forced into exile by the same law that had entrapped Chaminade; that is, for mistakenly appearing on the list of emigres. Only after six years of separation was the Baron able to join his family.

Called to Religious Life

at an Early Age

Shortly after the return of the family to Trenquelléon, Adèle embarked on a twofold career of spiritual growth. When she was not yet 13, she pestered her brother's tutor to give her a personal Rule of Life to prepare herself for the Carmelite vocation she so ardently desired to follow. By the time she was 15, she and a small group of friends had formed an association of prayer and support to promote their own spiritual growth and to prepare themselves for a good death.

Given the health hazards of the time and the ever-present possibility of renewed anti-Catholic persecution, it was not unusual for even young girls to think seriously of their death. This spiritual union spread rapidly and soon counted some 200 young women scattered over an area the size of the state of Ohio.

"Chere Adèle," as she was called, was its heart as well as its official leader and solidified their bonds by extensive letter writing.

By 1810 a number of these young women, like a number of the young men and women of the Sodality of the Madèleine, were looking for some form of religious life. By 1814 their plans had taken clear shape.

After the abdication of Napoleon and the death of her paralyzed father, Adèle was able to move freely and openly and put her plan into motion. Under Chaminade's prudent guidance and with the encouragement of Bishop Jacoupy of Agen, she and her companions in 1816 inaugurated their religious community living: the Daughters of Mary.

Like the Sodality, the community saw itself as called to give its members mutual support, to engage in Christian outreach to the world, and to carry on Mary's mission of birthing Christ in every age.

They integrated remarkably well the characteristics of the contemplative life of the Carmelites (to which Adèle had always been attracted) and the active missionary thrust of the Sodality.

After the foundation of the religious community, the Sodality continued to be a primary concern of the Foundress.

Though church law of the time required that women religious be cloistered, each of the five convents founded during her brief 12 years in religious life was the center of a Sodality for Young Women, a Married Women's Sodality, and a Third Order Secular which carried on the community's mission beyond the walls of its enclosure.

Foundation Built for the Marianists

For years she looked forward to the day when a Third Order Regular could be founded, so that the mission of the Sisters might reach those neglected rural areas with which she had been so familiar.

Only in 1836, eight years after her death, was this dream realized. The Daughters of Mary and the thriving Third Order Regular were combined in 1918, when new church law redefined them as "religious institutes."

From among the members of the Sodality came also the first nucleus of the Society of Mary, founded in 1817.

Dedicated to the mission of Mary and centered on conformity with her son Jesus, the "male religious of our Order," as Adèle called them, gave themselves to various works of ministry.

Dedicated to the mission of Mary and centered on conformity with her son Jesus, the "male religious of our Order," as Adèle called them, gave themselves to various works of ministry.

With the foundation of the Society of Mary, the three branches of the Marianist family — Sodality, Daughters of Mary and Society of Mary — were effectively constituted.

They found their unity in the person of Chaminade, who was head of all three.

More importantly for us, they found their unity in a common spirit flowing from the personality and insights of three remarkable people.

Today these foundations are known as Marianist Lay Communities, the Daughters of Mary Immaculate, and the Society of Mary.

The legacy of the three founders continues in our contemporary world, in the concern for the dynamic spiritual development of the members and in the outreach to the most impoverished and needy segments of our society.

With Faith and Tenacity, She Devoted Herself to the Marginalized.

Marie Thérèse, the eldest of 11 children, was of a noble, but relatively poor family. Her father, a lawyer, apparently was not skilled at being a business manager and had to sell various parcels of the family's property in order to make ends meet.

All that remained for Marie Thérèse's inheritance was a portion of her mother's estate, a country home and farm at Pian en Medoc, some 12 miles northwest of Bordeaux.

Born and raised in Barsac, she moved to Bordeaux with her family when she was 12. Very close to her mother — they related almost as equals — she became head of the family when her mother died in 1785. When nobles were forced out of the port cities in 1794, she retired to the family estate at Pian.

The pastor at the local church there was a constitutional cleric, so she refused to attend services. But she remained on good terms with the man and was instrumental in having him renounce his civil oath. With his departure, the parish church was abandoned; Marie Thérèse filled this void, and she became the heart and soul of the parish community for the next six years.

She gathered the parishioners for prayer, religious instruction, family counseling, and secret Masses celebrated by disguised and fugitive priests.

For all practical purposes, she was the "pastor" of the flock and was dearly beloved by all. In fact, when the French Revolution ended and priests could function in the open again, she had a hard time persuading "her" parishioners to go to the church again instead of coming to her.

Contacts with Father Chaminade

She kept in touch with Father William Joseph Chaminade during his three-year exile from 1797-1800. On his return she worked with him to develop the Sodality.

But her major work after 1800 was breathing life back into a badly needed service in Bordeaux: providing a place to live and an opportunity to change for the many prostitutes who wished to redirect their lives.

This work had begun before the Revolution by two of her friends. When calm was restored, one of them, Jeanne Germaine de Pichon, took it up again.

When she approached Chaminade to ask for Marie Thérèse's help, his response at first was negative; he had counted on Marie Thérèse for his work with the Sodality and was unwilling to let her spend energy on something else.

On second thought, he left the decision up to her.

She at first would not hear of it. But, after a couple of visits to the house where the prostitutes had been sheltered, Marie Thérèse changed her mind.

Faith, Energy

and Determination

Even though she had been in poor health since her birth almost 50 years before, she approached her work with incredible energy, determination, compassion and creativity.

When the number of prostitutes proved too large for different rented locations, she made a leap of faith.

Without funds, but with great confidence in God, she purchased at auction a former convent, named it Maison de la Misericorde (the House of Mercy, or Loving-kindness), and took in as many prostitutes as it could hold — eventually up to 400 at one time. The only condition for entry was that the women wished to change their way of life.

The women came freely. They stayed freely. And despite overwhelming obstacles and difficulties, the work prospered.

Through all the years until Marie Thérèse's death, Chaminade was at her side with his encouragement, fund raising, spiritual guidance and personal friendship.