The human context

Miriamne Krummel was in an airport in Chicago, on her way to St. Andrews, Scotland. The UD English professor’s destination was not the Old Course, where golf has a 600-year history, but the University of St. Andrews, which is older than golf, for a conference on John Gower, a poet and friend of Geoffrey Chaucer. Gower and Chaucer lived before St. Andrews was founded.

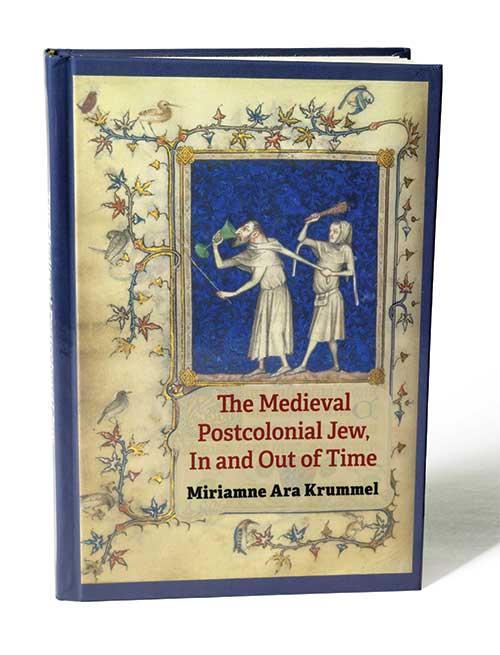

Krummel knows a lot about old things. A medievalist, she is working on her fourth book.

Navigating the airport presented Krummel with 21st-century frustrations. Coming to her assistance was a helpful United Airlines employee. He happened to be in a wheelchair. While in Scotland, she visited

a castle where a helpful guide distributed earphones to visitors. He, too, was in a wheelchair.

“Two people. Two different countries,” Krummel said. “In some previous times, people like them would have been considered nonfunctional.”

Among the courses Krummel teaches is Foundations in Disability Studies. (Students who take that course and three other related courses in various disciplines from the sciences, social sciences, arts and humanities can receive a minor in that emerging discipline.) “The course for this fall filled up within days,” she said. Students studying health and sport science showed considerable

interest.

Besides covering the theory of disability studies, students learn of people’s experience with disabilities through literature dating as far back as the Middle Ages. “Students are surprised,” she said, “to learn of what people then were thinking about.” But in Chaucer’s The Book of the Duchess, characters face mental and psychological issues such as depression, sadness, confusion and what Krummel called “the ultimate disability — death.”

Also from a previous century (the 19th) is Hide and Seek by Wilkie Collins, credited by some as the founder of detective fiction. The novel’s main character is deaf, and others have disabilities. “One seems to have what we would label ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder),” Krummel said. “The course’s contemporary readings have more specific words for conditions.”

Alan Shapiro’s 1997 Vigil is a memoir of the last year of his sister’s life. He writes of her getting cards and of offering to read them to her. She tells him not to read the messages printed on the cards but just the words that the senders themselves wrote. “Even if those words were simple, they were important because they were from that person,” Krummel said. “I want students to realize how important, especially when a person is sick and dying, the human context is.”

A Zoom visitor to the class last year was Shahd Alshammari, whose 2022 memoir, Head Above Water: Reflections on Illness, chronicles her experiences as a Kuwaiti woman with multiple sclerosis. “She was engaged to a man with MS,” Krummel said. “But when his family learned she also had it, the engagement was called off. Society viewed her as unmarriageable.”

She had been told by doctors she wouldn’t live past 30. She did. And became a university professor.

Krummel also has MS. Doctors also predicted an early death for her and warned her not to have children. She outlived their prediction; and her daughters, Yetta and Shoshanna, now 18 and 13, are healthy. She observed how some things have changed since they were born.

But about society’s attitude toward disabilities in general, Krummel believes that “there is almost a fear. We want to keep away from ‘those people.’”

We tend to see what’s wrong in the world as something outside ourselves. For many of the world’s problems, Krummel said, “We want a bad guy, a devil. There is evil in the world, but it’s not from such a person; it’s from a choice we make within ourselves between good and evil. It comes from our minds.”

Good also comes from choices, often from little contagious ones.

“I jog,” Krummel said, “not well, but I try. It’s more like a schlep. Sometimes a car will give me extra room. I wave. They wave back. I give dog walkers some extra space. Some people open doors for people with canes. Some don’t. They’re schmucks; not evil, just jerks.”

"Some people open doors for people with canes. Some don’t. They’re schmucks; not evil, just jerks.”

Krummel picked up Yiddish from her mother, her maternal grandmother and her grandmother’s friends. That influenced Krummel developing interest in languages from the Middle Ages to the present; it had a ripple effect, as acts of kindness do. Of that effect she said, “I hope I’m influencing my students toward the good.”