Blogs

Learning as a Holistic Process: Quick & Easy Ways to Teach with Context

By Hannah Jackson

Have you spent years carefully curating the instructional materials for your course: a beautiful collection of felicitous readings, riveting primary sources, and files upon files of supplementary gold? Yet still, your students (the ones that do the readings, that is) seem to be missing something. The classroom discussions are just not as rich as you’d hoped and students don’t seem to glean much from their independent reading. If this sounds familiar, your missing link may be contextualization.

Your Experience / The Student’s Experience

In 1972, two professors emeritus named John Bransford and Marcia Johnson conducted a study evaluating the importance of semantic context for comprehension and recall of a text.

Semantic context is the meaning given to words of a text due the surrounding content and implications, rather than their definitions.

Bransford and Johnson say that when students read, they, “Create semantic products that are a joint function of input information and prior knowledge.”

Here’s an example text I wrote inspired by the study. Read it and see what you make of it.

First, you will need to open the receptacle. Add the contents of the portable vessel into the receptacle, being careful to sort by visual characteristics. Also to the receptacle you will need to measure and add necessary liquids for ablution. Close the receptacle and assess your options for pace, fill, and calefaction.

Okay, now what if I told you that the above paragraph is about putting laundry in the washer? Read it again with this in mind. It makes a lot more sense, right? (Though I promise I would never teach someone how to do their laundry like this.)

Essentially, this 1972 study found that when students are not given enough semantic context before a reading, they are more likely to be put in an active “problem-solving situation” in which they have to figure out how to mish-mash the new information into some kind of schema or organization that already exists in their brain. The student is actively searching for a situation in which the new reading makes sense. However, with sufficient context provided beforehand, the student then has the brain capacity for “meaningful processing of information” to occur. This led to much, much higher levels of comprehension for the students who received context before reading.

When students are not given enough semantic context before a reading, they are more likely to be put in an active “problem-solving situation.”

Remember, your prior knowledge is not your students’ prior knowledge. You know a lot about what you teach and have ample experience in your field. Something that might seem basic and introductory (or obvious!) to you may be a totally new domain to your students. Some contextual information to preface your learning materials is not only recommended, but essential, for optimal student learning.

Contextualized Learning

Contextualized learning plays off the idea that, “Words have psychological properties—subjective characteristics such as the level of concreteness or imageability—which affect retention” (Godwin-Jones 2018). Nobody learns anything in a vacuum, and the best learning happens when connected to real-life experiences, prior knowledge, and other meaningful schemas that already exist within the student’s mind. Learners process information in a way that makes sense to them and in accordance with what they have already lived. According to The Center for Occupational Research and Development, “The mind naturally seeks meaning in context by searching for relationships that make sense and appear useful.”

Educational theories relating to context, schema, and contextualized learning have been around (and have been evolving) for decades. The ideas themselves can be quite vast, but the classroom application is actually quite simple. Let’s take a look first at an example of what not to do in your Isidore site. Then, we’ll move on to view a few ways to provide context for your readings.

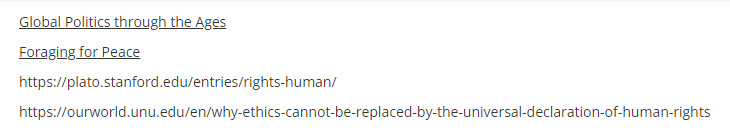

What to Avoid

This image shows an Isidore site with no learning context. The links are listed without explanation and the section is untitled. There are no descriptions or headers. Some URLs are simply copied into the text box without clickable links or a clear article title. This is the course equivalent of packing for a beach trip without bringing a swimsuit, towel, and sunscreen. Don’t do this. If you have quickly dropped a few links in Isidore like this before, it’s okay. Most of us have. But, are there much, much more pedagogically sound ways to present instructional materials? Yes! Keep reading.

A Little Bit Better...

This image shows improvement. The readings are preceded by a title and a brief introduction. The article links are all hyperlinked to their title (Julianne wrote a great blog to tell you everything you need to know about linking in Isidore), giving students a bit of information as to what the readings are. There are even icons next to the links showing students what type of document they will be opening. (Reach out to us if you need some help using these icons– we would be thrilled to show you.)

Now We’re Cooking with Gas!

There is no single correct way to give context to your materials. Designing your course is a process that (quite literally) holds endless opportunities for content delivery. If you are ever feeling stuck or bogged down by the prospect, send us an email at the Center for Online Learning. We would be happy to help. The following examples, however, are all great starting places.

Incorporate an instructor speech bubble to share some of your thoughts, past experiences, or important notes relating to the content you are asking students to interact with!

Incorporate an instructor speech bubble to share some of your thoughts, past experiences, or important notes relating to the content you are asking students to interact with!

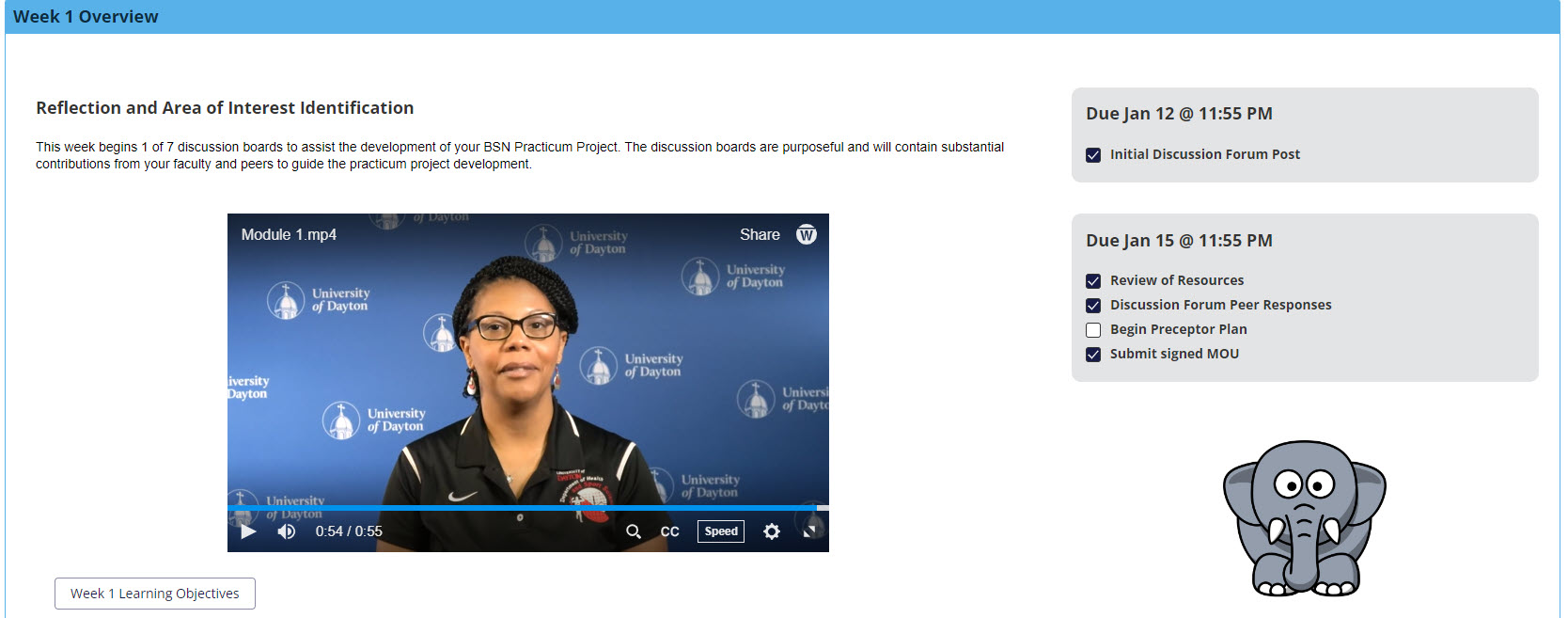

Dr. Erica Hunter's nursing course is seen here with an introduction video, a short written introduction, two checklists, and learning objectives for her weekly module. Introduction videos are a wonderful way to share some personal anecdotes and contextualize the incoming material personally. These are particularly essential when your course is taught online and asynchronously. These short videos can build instructor presence as well as activate prior knowledge or tell about your personal experience relating to a module. The Center for Online Learning can help you to film, edit, and upload videos– just send us an email to schedule an appointment.

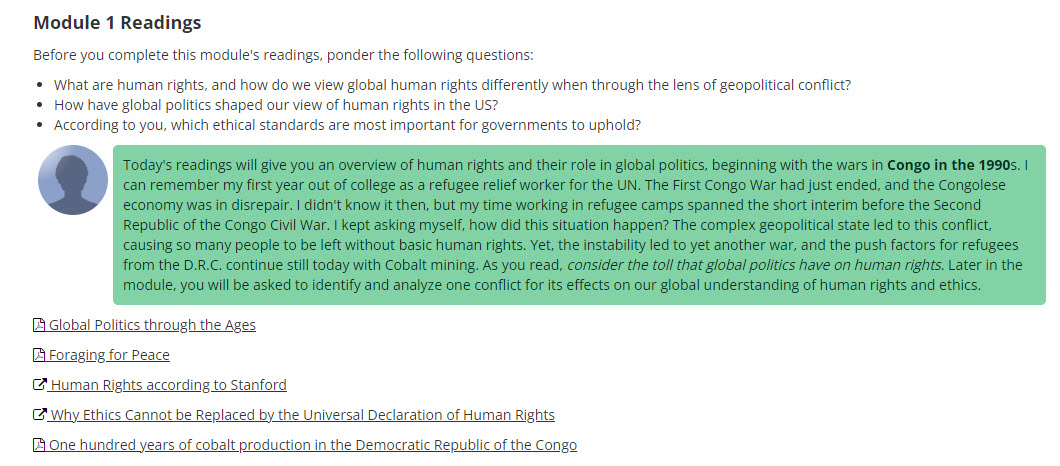

This image shows another simple implementation of contextualized learning. Give the section a header (Module 1 Readings, for example). Link all reading items with their titles displayed. Then, write a meaningful introduction to the readings. You can include any of the following in your introductions:

- What to expect in the following content

- The topic of the material

- How this content relates to something learned in the class before

- How this content relates to your or your students’ experiences in the field

- How this content relates to a personal experience of yours as a subject matter expert

- A short story or anecdote related to the content

- Questions to ponder while reading

Providing students with a link to prior knowledge, experience, or learning doesn’t have to look fancy. It just needs to be present, meaningful, and consistent!

As you make this small switch to providing personalized context alongside your instructional materials, you may start to notice more students speaking up in class discussions and more readings referenced in papers. It is a tiny change, truly, but its effects are profound. The context gives learners the stepstool to jump on board and begin schematizing. The idea is to get more mileage out of the same readings you’ve always had, as they will be consumed with more thorough comprehension and derived meaning.